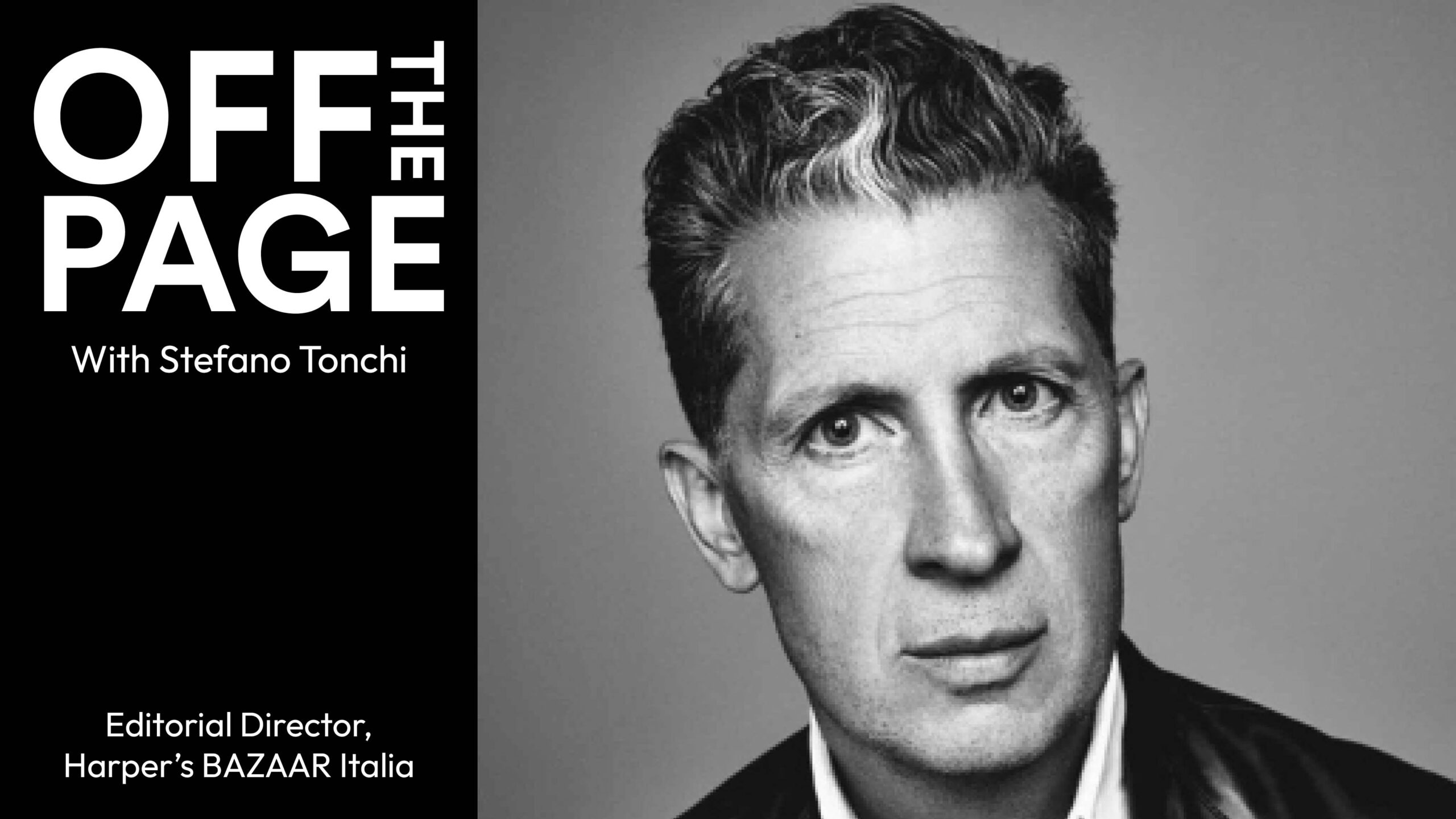

Welcome back to “Off the Page,” our interview series spotlighting the editorial voices behind Hearst’s global brands. In this second installment, Harper’s BAZAAR Italia Editorial Director Stefano Tonchi shares how he’s shaping a legacy title for a new era. Since stepping into the role in 2024, Stefano has guided the brand’s evolution, helping to shape a new visual and narrative identity that feels both collectible and contemporary.

In conversation with Kim St. Clair Bodden, SVP, Editorial & Brand Director of Hearst Magazines International, Stefano reflects on the enduring value of print, the dialogue between fashion and culture, and the quiet power of curiosity as the driving force behind his creative vision. He also shares a personal reflection on Giorgio Armani’s legacy—a reminder, he notes, that true revolutions in fashion need not be loud to be transformative.

You have such an illustrious career and are still very much committed to exploring the intersection of fashion, culture, and media in new and provocative ways — from legacy print to curated exhibitions to entrepreneurial ventures like Palmer. As you look ahead, what excites you most about your role as Editorial Director of Harper’s BAZAAR Italia, and what continues to drive your curiosity and creative risk taking in an industry that is constantly reinventing and redefining itself?

When I took on the role of Editorial Director at Harper’s BAZAAR Italia, I was fascinated by the idea of reimagining what a legacy publication could be. Earlier in my career, I helped lead some of the most successful mainstream magazines, including Esquire, T Magazine, and W. But the publishing landscape has since shifted with the advent of digital innovation and social media. Many magazines tried to compete with these new platforms and, in doing so, lost sight of their essence, their readers, their mission, what made them relevant and resilient.

I experimented with niche publishing and launched projects that were highly focused—geographically and socially, horizontally and vertically—and of great quality in both the content and the execution. It worked out very well financially, and I wondered whether that model could be replicated on a larger scale.

I never believed that digital and social would kill the print business, but, on the contrary, I firmly believe that print remains the centerpiece of any publishing brand – and, when managed correctly, can remain a profitable asset. Magazines need to own their field and maintain their uniqueness, the long-form content and expansive image portfolios, if they want to compete in other fields where they often arrive late and unprepared.

The print magazine business is among the few businesses that have hardly changed in a century. Too many copies are still being printed and distributed like they were a hundred years ago: printed on cheap paper, delivered to subscribers late and in unattractive plastic wraps, and sent to newsstands that either no longer exist or no longer wish to carry them. Magazines are luxury goods that should look and be presented and priced as such. Look at what advertisers produce and send to their customers…look at what Assouline Publishing did when they could not find a way to sell their books: they became more and more luxurious and opened their own stores!

You were born in Florence and now divide your time between Milan and New York—two cities with distinct fashion languages and cultural rhythms. In an increasingly globalized industry where trends travel at the speed of a swipe, what elements still feel inherently Milanese or innately New York to you—in terms of attitude, pace, and the way people dress? And how does that quieter, Florentine sense of heritage and detail continue to shape your point of view amidst it all?

The world is becoming increasingly homogenous, and there are now very few differences between shopping in Florence, Milan or New York. The same branded stores crowd the best shopping streets and offer the same products. This has been the rule, but things are changing. I anticipate a return to specialty stores, where the selection is curated by a great personal stylist, and a return to smaller, more human, fashion stores with unique pieces. Unless you are in the business of selling wallets, lipstick and key chains—though, are there still keys?

To really understand the soul of a country, you need to travel to the areas where you can still see what the local style is. When I am in Italy, I have a habit of visiting towns like Parma, Reggio Emilia, Lucca or Ancona. Suddenly you understand what the differences are between Italian style and French style. In the USA, I see the luxury market focusing more on towns which are home to enclaves of affluence and influence: Palm Beach, Aspen, East Hampton and Nantucket, as well as cities like Austin or Nashville. My motto is: follow Hermes and Cucinelli’s new store openings, and you will find the best possible audience for your publications.

You’ve written poignantly about growing up in a time when self-expression—especially through fashion—could still happen in secret, away from the public eye, in “tight and secretive tribes.” Today, young people perform their identities online in front of invisible, ever-watching audiences, where every outfit is content and every post a performance.

So, as both a fashion authority and a father, how do you see this era of hyper-visibility and aspirational conformity shaping the next generation’s relationship with style, identity and even self-worth? Is fashion still sometimes a tool for rebellion and discovery, or has it become a uniform for digital survival?

I always say that I do not envy the new generations, nor the social pressure they are exposed to anytime and everywhere. The pressure to conform has never been stronger, and the strength of rebellion so weak. But we need to have hope. Maybe fashion is no longer the place where creativity and rebellion will happen again; maybe other art forms— visual arts, music, design—will offer better tools of self-expression.

Still, the relationship between the body and clothing will remain central to the human experience. How we dress will still play an important part in expressing who we are, who we want to attract and from whom we want to distance ourselves. Fashion as a form of human expression will not disappear. I do not see a future with people in uniforms. I don’t even want to think about it!

Harper’s BAZAAR Italia team at Milan Fashion Week.

Today, fashion is not just on the runway but streaming on Netflix, in biopics, in reality TV, and in endless social feeds — a cultural omnipresence you’ve described as both “a blessing and a curse.” How do you see this explosion of fashion documentaries and celebrity-led storytelling affecting the authority, authenticity, and critical discourse around fashion? Is there still space for serious fashion journalism in a world where everyone wants a front row seat?

Fashion has become part of a larger cultural discourse. I always believed that fashion was part of the cultural landscape, one of the liberal arts, a form of invention and expression like literature or painting. Many, however, have regarded it merely as a craft to be studied by ethnologists, or a business to be taught in economics and marketing schools. Truly, it encompasses both industrial design and craftsmanship, imagination and creation, but also marketing and finance. Finally, we are seeing a kind of “historization” of fashion: we see fashion exhibitions in mainstream museums; movies and TV series about fashion designers in theaters, on our phones and in our living rooms. Not everything is of quality and worth our attention, but they all together move forward the knowledge of this art form.

The digital revolution has exploited this omnipresence of fashion in every form of media: fashion now looks so easy, so colorful, so entertaining. The monster needs to feed the monsters, but it is no different from what we see in sports or cinema. Everyone is a critic, an author, an authority. Every opinion can go mainstream, and the audience has the power in their hands. But again, after many years of dictatorship of the audience and the law of the consensus, I can see the return to a more balanced power dynamic between those who have studied and have experience, and the dilettantes and new fresh opinion leaders.

Many of my older colleagues keep saying that fashion is dead, but I have never seen so many people interested in it. Fashion has become big and excessively popular; what was once a privilege of the few is now accessible to everybody. The democratization of fashion may have changed the nature of fashion and the discourse surrounding it. In my youth, fashion was very much about the clothes and the very few who could afford them. Today, it is about much more: the clothing, yes, but also celebrities, cinema, television, art and so on. The future of fashion lies in finding the right balance.

Diversity, disruption, and discovery have always been central pillars your philosophy. How do you evaluate progress (or resistance) in those areas today across fashion media and institutions?

In recent decades, we have lived through great changes and moved forward to a better understanding of justice, democracy, and human rights. In the United States, and across much of the Western world, we have never had this kind of social freedom. Gender and race have become central to public discourse, and people have taken to the streets to fight for their beliefs.

At times I wonder, have we gone too far? Perhaps society was not ready for so many changes and for some forms of extremisms that have consequently emerged in the past few years. Have we focused too much on ourselves, while neglecting much of the world, where women, LGBTQ+ people and racial minorities still have no rights? Now is the time to reflect, think globally, and defend what we and our parents fought so much for. From my 30-year experience in publishing, the daily silent practice of accepting diversity, pushing disruption, and encouraging discovery is much more powerful than loud declarations or performative displays of these ideals.

You witnessed the early rise of Giorgio Armani firsthand, attending his shows in Milan during the transformative ’80s when he was already “King Giorgio” — a figure whose vision shaped not just fashion but the very identity of Milan. Considering his recent passing, how do you reflect on Armani’s lasting impact on fashion as both an art form and a cultural force? And what lessons from his minimalist, timeless approach do you see as especially relevant for today’s rapidly changing fashion landscape?

Giorgio Armani’s legacy is incredibly rich and still to be completely appreciated. He really made ready-to-wear popular, democratized good taste, and made luxury feel within reach. He redefined the relationship between the body and clothing, for both men and women, giving them comfortable but elegant uniforms. He reinvented how a woman could dress for receiving an Oscar!

He built a brand out of his sole talent and never compromised his aesthetic vision. I grew up looking at him, not always in agreement, but surely with deep respect towards his point of view. Recently, I have been thinking that he was a much more complex figure than he appeared, a man who grew up in a time when being homosexual and successful was nearly impossible, somebody who lived through the AIDS epidemic and the years of repression and darkness that followed it.

He made Milano a fashion capital and Milanese synonymous with stylish. His lasting lesson is that a revolution needs to be loud and offensive to change people’s minds—sometimes it begins simply by changing the way people dress.

Stefano Tonchi, with Giorgio Armani, at the designer’s 40th anniversary celebration. Courtesy of Armani.

Harper’s BAZAAR Italia has brought on Michael Amzalag and Mathias Augustyniak of M/M (Paris) as its new creative agency, effective with the September 2025 issue—tasked with transforming the magazine’s visual identity both in print and online. With that in mind: what fresh visual and narrative strategies do you think M/M will introduce that differ from previous directions? How might their multidisciplinary, experimental approach challenge or redirect Harper’s BAZAAR Italia‘s role in fashion publishing? And in this new alignment, what would you expect their signature voice (or disruptive edge) to be—especially in a landscape where magazine aesthetics are under pressure to both conform and stand out?

From the beginning, my conversations with the creative director duo M/M, whom I admired for years and hired to re-imagine BAZAAR Italia, were not about creating another niche publication, but stretching the idea of what a mainstream magazine could be. We thought about the structure of the magazine, the look and the size, the quality of the paper, the images, and the words. We wanted to create the best possible luxury product available at the traditional newsstand, in the mainstream magazine rack.

M/M wanted to reinvent the reader’s experience through the physicality of the object—larger, heavier, collectible—and through the uniqueness of its content, offering an experience for the eye and the mind of the reader, and not following old traditions. Why not place the cover story, main photo portfolio, and in-depth interviews directly after the table of contents? We want the editorial content that we publish to be substantial, relevant, definitive: 24- to 36- page long photo portfolios, 10,000-word exclusive profiles, opinion essays and surprises; everything that cannot, and should not, be on a smartphone. We want to be the best, not the first.

In the well, M/M also introduced two new sections inspired by the heritage of the Harper’s BAZAAR magazine published in Italy in the 1970s: the Gran Bazaar, a kind of cabinet of curiosities, smartly edited and truly informative; and the Mind Bazaar, a collection of op-ed and short essays by influential writers, philosophers, historians, and curators.

We want to create a print experience that does not compete with the digital media experience but complements it and enhances the power of the brand. Of course, we are not forgetting digital; rather, we treat it as a very different form for delivering content, organized following different rules than for print. We’ve changed the look of our digital platforms to feel more organic with the imagery and design of the print magazine. M/M are known for their typography, and for BAZAAR Italia they created a new typeface, The Bazaar, inspired by the brand’s rich typographic heritage — a contemporary evolution that opens a new chapter in its visual history.

Looking ahead, what is your vision for the next decade of fashion journalism and publishing? What form(s) might storytelling take (e.g. immersive media, AI, archival repurposing)? What role do you hope to play in shaping that future?

Looking ahead to the future of media, I think that we will learn to make better use of all the tools that technology has to offer. AI can be very useful for research and production, but it cannot substitute the human voice in writing and creating content. Digital outlets will evolve, and the content they deliver will adapt to new forms, but they will not substitute platforms (maybe still print or something else!) for long-form storytelling and exceptional visual experiences. Reality will merge with immersive experiences, but we will still look for the touch and feeling that only humans can offer.

My role as an industry leader is both to learn and to teach how to use technology and not become its victim. My hope is that quality and legacy will return to be relevant, that trust and accountability in both and behavior will regain their true value.

From your perspective, what is the greatest value of being part of Hearst’s global network — and how does the collaboration among global editors enhance the strength and distinctiveness of Harper’s BAZAAR Italia?

A decisive factor in getting me back into working in a large media corporation was the guaranteed independence of BAZAAR Italia and the capacity to produce local content for an Italian audience while creating original fashion portfolios for the international community. Within Hearst’s global structure, there has been a strong commitment to allowing each editor to maintain their own style and editorial signature — recognizing that every country has its own cultural identity, audience, and market dynamics. This approach has proved highly effective, and the success of BAZAAR Italia is an indication of the strength of this vision.

At the same time, there is a continuous and dynamic exchange with other Harper’s BAZAAR editions—keeping communication channels open, sharing content and imagery, co-developing international projects, and leveraging the global power of the brand. What is crucial is that these collaborations take place on a foundation of mutual respect and creative parity, allowing each local edition to adapt global ideas to its own context and sensibility.

Quick-Fire Round…

City with the best-dressed people?

Seoul.

The one item you’d rescue from your closet in a fire?

My original 1997 Prada nylon backpack (useful for a quick escape with your essentials).

Most stylish film of all time?

Qui êtes-vous, Polly Maggoo? By William Klein.

Piece of advice you got in fashion—and actually followed?

No socks with loafers and match your belt to your shoes.

Luxury you secretly find overrated?

Cashmere and exotic skins.

Fragrance: Oud or citrus?

Complex citrus.

Hotel vibe: Old-world palace or futuristic glass cube?

Old-world building with minimalist interiors.

Last question…when one looks back at your legacy in this industry, what do you hope truly endures? What part of your work, your vision, or your presence in this industry do you hope continues to resonate?

My role as an editor has always remained the same, yesterday as today: to nurture talent, create platforms for expression, remove obstacles, find resources, encourage and support the next generation of fashion photographers and writers. It really makes me happy and proud to see so many of the people I have worked with go on to build remarkable careers and great success.

I think my legacy is having created publications where fashion was always part of a broader cultural discourse, presented in the context of art, music, cinema, design—and where the images were always as important as the words, so that each issue would become both a visual and an intellectual experience. Everywhere I’ve worked, I have brought an open mind and an interdisciplinary curiosity. Yes, probably, curiosity should be my legacy, the most under-appreciated quality.